A "From-Scratch" Word2Vec Playground in PyTorch

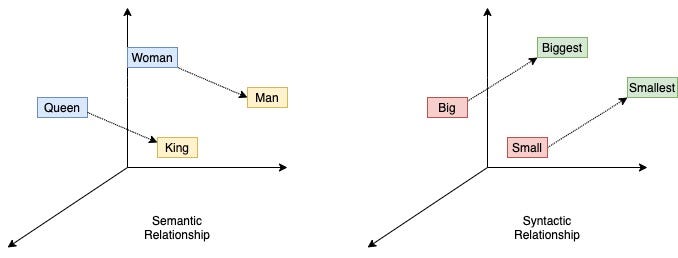

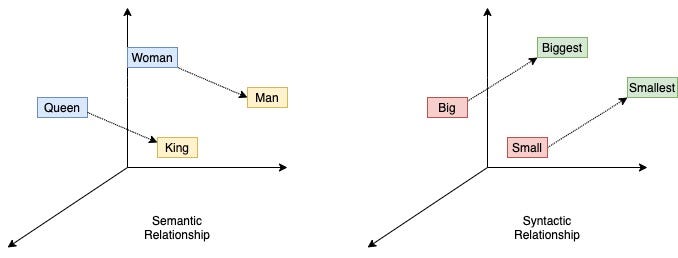

Word embeddings are dense vector representations of words, but have you ever considered their limits? If a 300-dimensional vector represents a word's "concept," how many truly unique concepts can it hold? If "unique" means perfectly orthogonal, the answer is just 300. Yet vocabularies contain tens of thousands of words. How can so few dimensions capture so much meaning?

The magic lies in high-dimensional geometry. In a high-dimensional space, you can pack an astronomical number of vectors that are *almost* orthogonal. This project demystifies the process by building Word2Vec (specifically, the Skip-Gram with Negative Sampling model) from the ground up, revealing how an algorithm can learn to navigate this vast "meaning space."

The Skip-Gram model works on a simple predictive task: **given a target word, predict its surrounding context words.** For example, given the word `fox`, the model learns a vector representation that is good at predicting nearby words like `quick`, `brown`, `jumps`, and `over`.

A naive approach would require a final softmax layer over the entire vocabulary—a massive computational bottleneck. The key optimization is **Negative Sampling**, which reframes the task into a simple binary classification problem. Instead of predicting context words, the model learns to distinguish between true `(target, context)` pairs (positive examples) and randomly generated fake pairs (negative examples). This is vastly more efficient.

The true test of the model is to inspect the nearest neighbors of various words. The results show both clear successes in capturing semantic meaning and fascinating "errors" that reveal biases in the training data.

Words closest to 'king':

- kings (similarity: 0.6130)

- throne (similarity: 0.5964)

- reigned (similarity: 0.5740)

- son (similarity: 0.5612)

- prince (similarity: 0.5282)

Words closest to 'computer':

- computers (similarity: 0.7196)

- hardware (similarity: 0.6161)

- machines (similarity: 0.6085)

- software (similarity: 0.5428)Analysis: The model successfully learned the semantic concepts, grouping words related to royalty for `king` and technology for `computer`.

Words closest to 'history':

- references (similarity: 0.5308)

- links (similarity: 0.5181)

- article (similarity: 0.4784)

Words closest to 'france':

- french (similarity: 0.6270)

- italy (similarity: 0.5540)

- partements (similarity: 0.5381)

- partement (similarity: 0.5164)Analysis: These "errors" are actually correct learnings of corpus artifacts. The model didn't learn the abstract concept of `history`; it learned the structural context of a Wikipedia article, where "history" sections are followed by "references" and "links." Similarly, it correctly associated `france` with `partements`, a tokenization artifact from the French phrase "départements d'outre-mer" in the pre-cleaned training data.

This project highlights both the power and the limitations of static embeddings. A word like "bank" will always have a single vector, regardless of whether it refers to a river bank or a financial institution. This is the trade-off. What if an embedding wasn't static? What if "bank" could move closer to "money" or "river" depending on the sentence it's in?

That leap—from a frozen dictionary to a living, context-aware language model—is exactly what architectures like the Transformer make possible, paving the way for the next generation of natural language understanding.

This project is an open-source playground. The code is heavily commented and modularized to encourage exploration into the geometry of language.